On October 27, 2024, the Ecuadorian military entered the small parish of Palo Quemado in northern Ecuador, temporarily militarizing the community for the third time in less than two years.

According to community residents, at least eight trucks and several vans arrived in Palo Quemado in the early hours of October 27. With several license plates covered, the vehicles reportedly carried officials from the Ministry of Environment, Water and Ecological Transition (MAATE) with the aim to advance a highly controversial environmental consultation process within the parish. If concluded, the environmental consultation – already suspended several times due to local opposition and community protest – would grant the Canadian-owned “La Plata” mining project the green light to advance towards the exploitation stage.

Military vehicles remained in the centre of the parish for the day and night, intimidating residents who expressed concerns for their safety. The military and police had to leave the area the following day because the local authority did not grant them permission to use public spaces and tables could not be erected for the consultation. Residents of Palo Quemado denounced the presence of “Junta de Defensa del Campesinado,” a group made up of people from outside the community who are hired to participate in the consultation process, and who have been accused of acts of intimidation in previous attempts to militarize the region

The project

La Plata, located in Ecuador’s northern Cotopaxi province, has been owned since 2019 by Vancouver-based Atico Mining. La Plata is currently in pre-development, proposed to extract up to 1000 tons of ore per day to process gold, copper, zinc, and silver.

La Plata is one of 27 Canadian mining projects in Ecuador and is one of the 14 gold and copper mining projects in the country designated as a “Security Zone" (Áreas Reservadas de Seguridad). Under this designation, state security forces may be used to protect mining projects in early stages of development. While these security zones are being framed as a response to “incursions by illegal miners or violent attacks on mining camps,” they are being used as a pretext for militarizing communities and escalating violence against protesters.

What’s at stake?

A significant portion of the local affected communities of Palo Quemado and neighbouring Las Pampas have firmly opposed mining for at least the past 40 years on the grounds that mining have already contaminated their watersheds and soil [defensoría del pueblo - amicus 2024, on file with MiningWatch Canada] and that new mining activities will threaten the integrity of surrounding ecosystems, air and water quality, as well as the social fabric of their communities.

The mining concession crosses urban centres including Las Pampas and Palo Quemado and overlaps with the Reserva Ecológica Los Ilinizas. The mayor of Sigchos, home to the parish of Palo Quemado, has denounced that the mining concession poses potential threats to the health of the ecological reserve and its flora and fauna. The impacted Indigenous, montubio (mestizo people of the countryside of coastal Ecuador), and campesino communities fear their livelihoods raising cattle and farming sugar cane for export to Europe will be negatively affected by water contamination.

While concerns about the impacts of mining have been documented for years, communities in Palo Quemado and Las Pampas have increasingly denounced the harmful social impacts they are already experiencing even before the project is operational. Since 2023, they have denounced increased community division, threats and intimidation, widespread criminalization of those in opposition, and violence on the part of security forces to advance an environmental consultation they view as illegitimate and discriminatory.

An environmental consultation imposed through violence

In 2023, former President Guillermo Lasso passed Executive Decree 754 which aims to formalize a process for environmental consultation with the public. However, it affords communities no rights to veto development projects on their lands and has been loudly rejected for being unconstitutional.

La Plata has been one of two test sites for this controversial process for environmental consultation. The second test site for the environmental consultation is with communities affected by the Curipampa-El Domo project, owned by the Canadian companies Salazar Resources Ltd. and Adventus Mining Corporation (recently acquired by SilverCorp Metals Inc). Affected communities in the canton of Las Naves in the province of Bolivar faced criminalization, intimidation and military repression in relation to their opposition to the project in 2023.

In Palo Quemado, following a first failed attempt in 2023 to advance the environmental consultation, the national government resumed consultation efforts in March 2024. Significant military and police repression ensued, when people protested the violent way the consultation was being imposed and its exclusion of many affected communities. At the time, local and national human rights organizations circulated video recordings on social media in which it appears the military were being housed within Atico’s compounds. At least 15 people were injured and one person left in a coma. As Amnesty International Canada says in its 2024 submission to the UN Human Rights Committee’s review of Ecuador, “more than 70 individuals, including Indigenous leaders and human rights defenders, faced criminal charges [terrorism charges] following the protests.”

Since then, many of the same environmental defenders charged with terrorism are also now facing charges of organized crime and criminal conspiracy.

Beyond the criminalization, the project and the attempts to advance an environmental consultation have caused deep family and community divisions, trauma and conflict within the communities between those who oppose and are in favour of mining. Ecuador’s Human Rights Ombudsperson visited Palo Quemado at the time to document the human rights situation during the environmental consultation. When the mayorship of Sigchos filed a court injunction against the consultation, the Human Rights Ombudsperson provided to the courts an amicus in which the office highlights the trauma children faced:

“Children and adolescents living in the communities of the parishes of Palo Quemado and Las Pampas have been exposed to situations of violence by watching videos on social media of the conflict which their parents, relatives, neighbours and themselves are facing, by listening to conversations about what is happening around them, by witnessing the deployment of police and military personnel in their neighborhoods, by staying alone in their homes while their parents are exercising their right to resistance and protest, by thinking about what will happen tomorrow, and by thinking about the future.”

The environmental consultation was suspended in March 2024, but the courts have now backtracked on that decision. The Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), the National Anti-Mining Front, and others have announced their intention to appeal the judge’s decision. Since then, fears are high there will be renewed efforts to carry out the consultation and, along with it, bring renewed state violence. The widespread military presence in Palo Quemado between October 27-28 proves these fears are well-founded.

Meanwhile, residents in Palo Quemado have expressed their strong opposition to all acts of violence and call for peace and unity.

Intimidation of communities

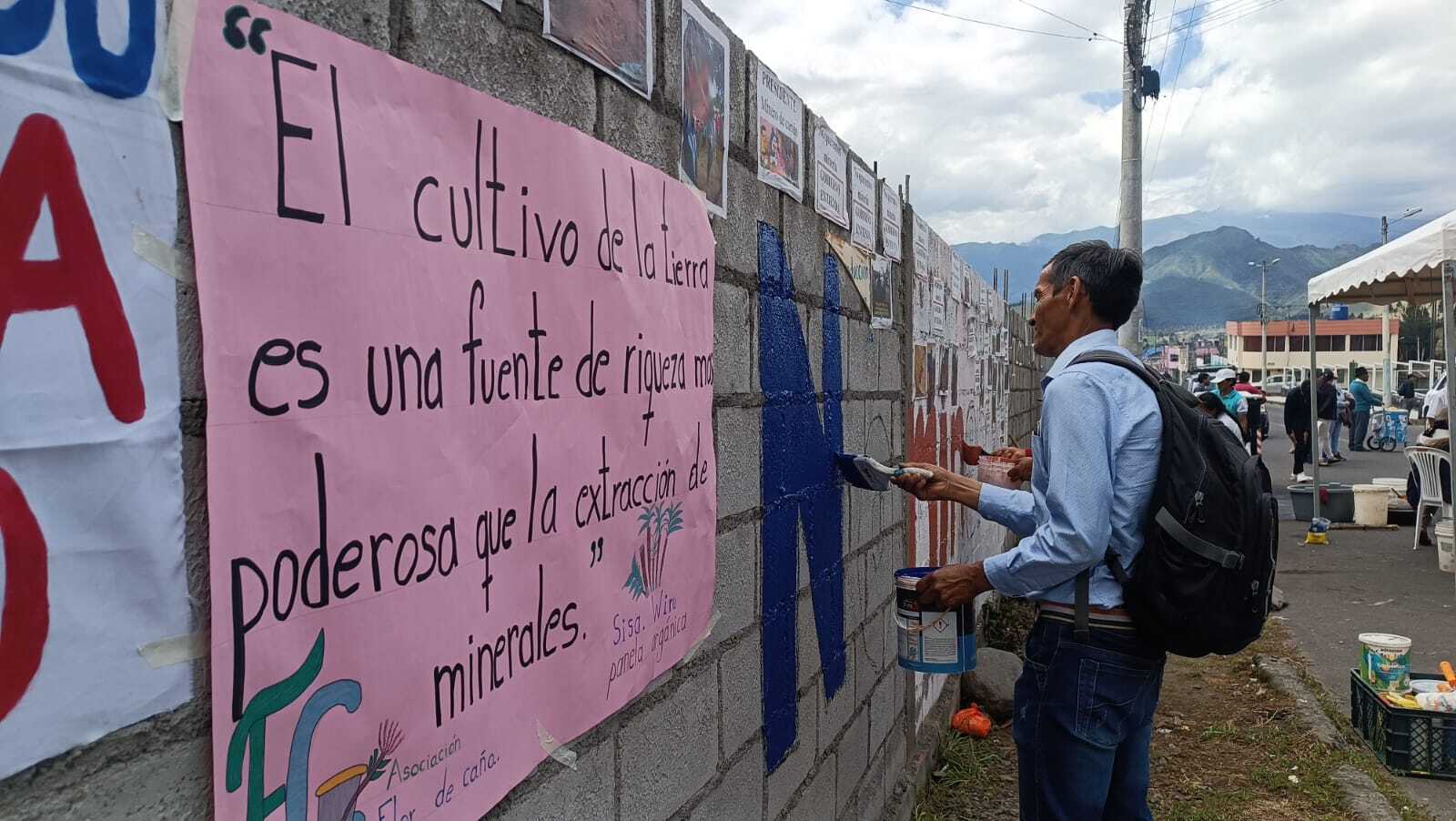

In addition to the criminalization of environmental defenders in Palo Quemado, members of local sugarcane cooperative Association Flor de Caña have also suffered acts of harassment and intimidation. They have faced an onslaught of harassment on social media, attempting to slander their reputation and disempower their struggle. As Rosa Masapanta, President of the Association, says, “I fear for my life, physical safety, and psychological health. During previous attempts to advance the environmental consultation, we noted a significant uptick in attacks on social media, especially threatening towards me. There were calls to violence, putting a price on my head.”

Atico Mining is also being accused of installing security cameras near the town centre. According to Yuly Tenorio, legal counsel for the Association Flor de Caña, the company is “implementing surveillance and monitoring strategies by installing these cameras under the pretext of security to create an atmosphere of fear in the communities.” Yuly is also the Coordinator for the National Citizens Observatory for Monitoring the Fulfillment of Human Rights and the Rights of Nature with regards to all phases of mining.

What does the United Nations and Canada say about the violence?

International human rights organizations and several United Nations bodies have denounced this process for environmental consultation for excluding many Indigenous Peoples and other potentially affected communities, for providing incomplete information, and for the violence under which the consultations have been carried out.

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk expressed his concern last year about the violence surrounding these projects, and underscored the right of Indigenous Peoples to be consulted on the use of their lands. He noted, “People directly affected by mining projects or activities must be heard, not repressed.”

Together with other UN experts, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders Mary Lawlor also wrote to the governments of Ecuador and Canada about the misuse of the judicial system against human rights defenders, underscoring Canada’s responsibility to protect and uphold human rights, and expressing concern that Atico Mining receives financial support from Export Development Canada.

Canada has not denounced the violence committed against Indigenous nor environmental defenders despite requests by civil society organizations to respect human rights and halt the promotion of Canadian mining in the country. On the contrary, during a special session of the Standing Committee on International Trade of the Canadian House of Commons as part of its study of the Canada-Ecuador free trade agreement negotiations, the current Canadian ambassador to Ecuador minimized the statements made by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. affirming “that [his] opinion […] was not well-founded.”

The use of state security forces to repress local opposition to mining is a growing trend in Ecuador and is happening within a context of a declared internal armed conflict and successive states of emergencies. According to Amnesty International: “These decrees from president Daniel Noboa are a continuation of a series of emergency decrees published by the previous presidential administration suspending a series of rights, including the right to freedom of peaceful assembly, as well as allowing both police and the armed forces a wider mandate to enter residences and premises to carry out searches, seize property and to access correspondence.”

Mining projects that aren’t even operational yet, such as La Plata, are already causing significant and potentially lasting harm – raising glaring concern as measures are put in place to dramatically increase Canadian mining investment, including through a new free trade agreement between Canada and Ecuador.

Zenaida Yasacama, vice-president of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador, has spoken out against the violence seen in places where there are existing Canadian mining projects. She recently joined a delegation of Indigenous women and environmental defenders from Ecuador to Canada to denounce the trade negotiations, and said during a press conference:

“We denounce the persecution and criminalization of environmental defenders and local communities in Ecuador, particularly in Palo Quemado, in Napo province, and in Shuar territory – where more than 100 people have been prosecuted. They are not criminals but rights defenders who are courageously resisting the advancement of the Canadian extractive industry in their territory. This resistance is taking place in a context where our right to free, prior and informed consent is systematically ignored.”

While the military may have left Palo Quemado for now, the Ecuadorian government has been clear in its intention to advance Canadian mining interests in the country, including in Palo Quemado. The Association Flor de Caña and others across Ecuador are asking the public to remain vigilant to further attempts to militarize the communities impacted by Atico Mining in the name of advancing an environmental consultation and to the ongoing intimidation and harassment they face due to their work leading awareness campaigns for the care of the land and water in the face of the threat of mining exploitation of the La Plata project.

Photo: A hand-printed sign is posted on a wall in Sigchos in March 2024 when communities filed a court injunction against the advancement of the environmental consultation. The sign reads: "Cultivating the land is a more powerful source of wealth than the extraction of minerals." Source: Associación Flor de Caña.