A new report by a renowned environmental lawyer concludes that British Columbia is “not yet a world leader” in its environmental reviews of proposed metal mines – despite the province’s claims to the contrary.

According to Premier John Horgan, “All mining projects, including those near British Columbia’s transboundary rivers, are subject to world-leading regulation and oversight.” But an analysis by legal expert Stephen Hazell concludes that it’s only the largest mines that are subject to environmental assessment under B.C.’s new Environmental Assessment Act, not the most environmentally dangerous – and certainly not all of them.

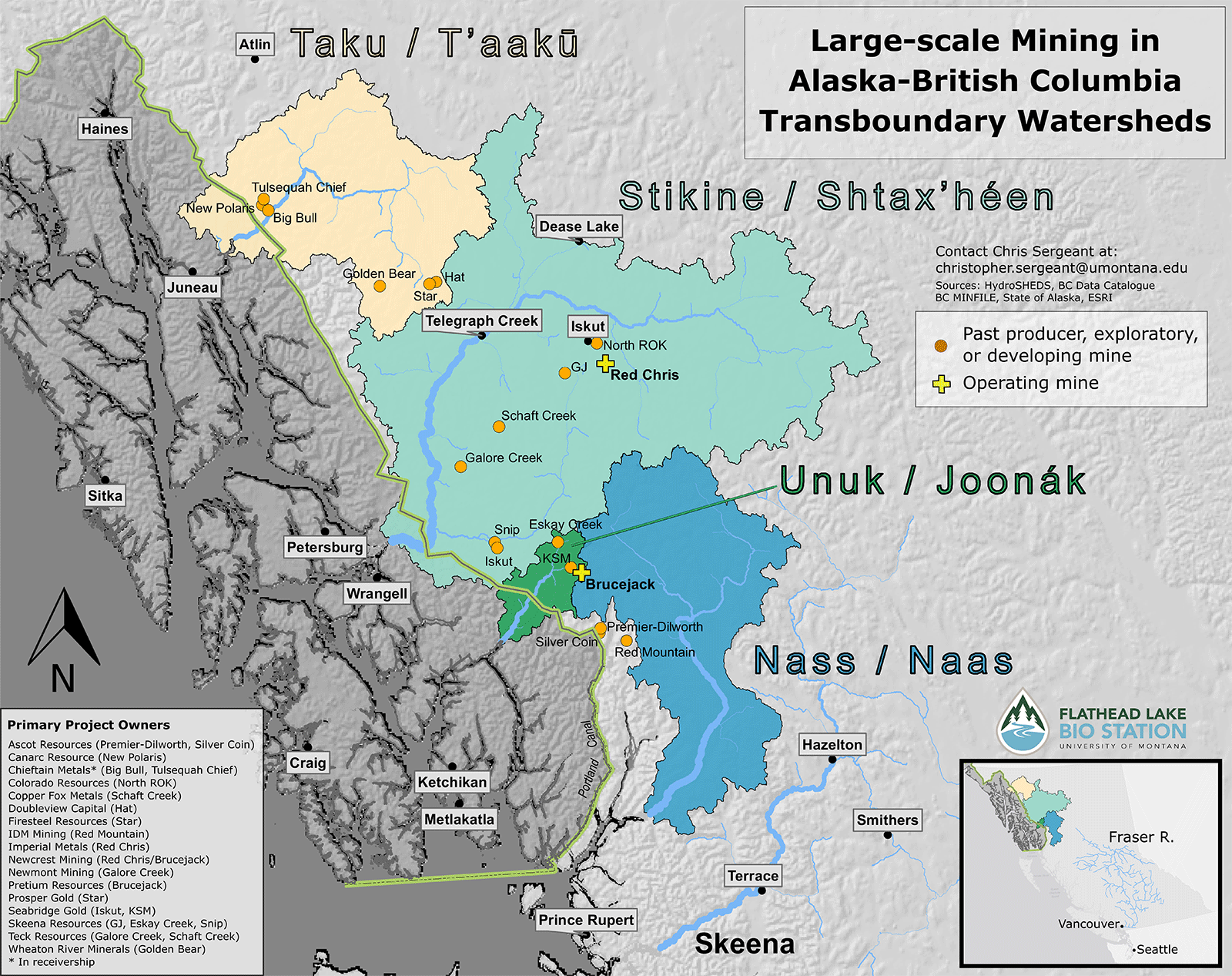

While mining is a significant part of B.C.’s economy, many operating mines currently discharge selenium and other pollutants into rivers that flow into the United States such as the Similkameen, Stikine, and Taku. Others threaten watersheds within the province, whether from routine effluent or from spills and accidents – potential, or in the Mount Polley case, all too real.

Environmental reviews, whether called ‘environmental impact assessments’ or just ‘impact assessments’, are an essential tool to determine the environmental, economic, social, cultural, and health effects of industrial development resource projects such as metal mines. They serve to mitigate adverse impacts such as water pollution, and they can also identify potential errors or risks in design and construction.

The report, “Not Yet a World Leader: Environmental Reviews of Metal Mines in British Columbia”, takes aim at the size limits that restrict the application of the Environmental Assessment Act (BCEAA), allowing mining companies to avoid assessments and proceed with new or expanded mines that are likely to have significant adverse impacts. These limits have been raised significantly with the new law. For example, a proposed mine with less than 75,000 tonnes of annual ore production is not required to undergo assessment. This is a massive change; the comparable threshold prior to 2019 was 25,000 tonnes. Likewise, the current law requires an assessment only for a proposed mine that would clear more than 600 hectares of land (6 square kilometres – 1/3 bigger than Stanley Park).

The report analyzes the environmental assessment laws of Washington State, Alaska, Northwest Territories and northern Quebec, and concludes that at least five B.C. mines that were likely to have significant environmental impacts, but did not undergo an assessment, would have been assessed under the laws of those jurisdictions: Elk Gold, Premier Gold, Copper Mountain Expansion, Yellow Giant, and Bonanza Ledge.

The report also notes that B.C.’s approach creates opportunities for “mining by instalment” strategies that allow large mines having significant adverse effects to be developed in stages, without assessment, so long as the initial mine and each subsequent expansion fits within the thresholds.

This means even more new mines and mine expansions may be developed in British Columbia without environmental review under the BCEAA, potentially polluting rivers that flow into the United States and adding to existing cross-border political tensions arising from current pollution from B.C. mine discharges.

The report recommends that the BCEAA regulation be amended to require review of any new metal mine, any expansion of an existing mine that has not been previously assessed, and any expansion of a previously assessed mine that disturbs more than an additional 50 percent of the land disturbed by that mine.

The report also notes that B.C. First Nations may fill this gap by implementing Indigenous-led impact assessments, as recently presented by the First Nations Energy and Mining Council, or by developing collaboration agreements for sharing decision-making on natural resource development, such as the B.C.-Lake Babine First Nation Foundation Agreement. The report recommends that B.C. and Canada provide funding to First Nations for Indigenous-led environmental reviews of projects, especially those not subject to federal or provincial assessment.

Finally, the report observes that international laws and standards apparently have not figured in B.C.’s decisions to assess metal mine projects sited on transboundary waterways. The Boundary Waters Treaty provides that waters flowing across the Canada-U.S. border shall not be polluted on either side to the injury of health or property on the other. B.C. has the most serious responsibilities to comply with the treaty given that the province is for the most part upstream of the United States. Likewise, the Espoo Convention creates an international standard providing for participation of affected citizens of a neighbouring country in an assessment by a host country of a project likely to have significant adverse transboundary impacts. The report recommends that Americans affected by a proposed B.C. mine likely to have adverse transboundary environmental effects have similar rights to participate in assessments as Canadians.

“Not Yet a World Leader: Environmental Reviews of Metal Mines in British Columbia” will be presented by the author, Stephen Hazell, at the International Association for Impact Assessment conference in Vancouver this Saturday, May 7, at 10:30 a.m. in Room 16 at the Convention Centre East. The report can be downloaded here.